Image by Lernert & Sander for the Dutch newspaper De Volkskrant.

Developing Reflexivity in Research. For this post see texts by Dr Christina Hughes from Warwick University

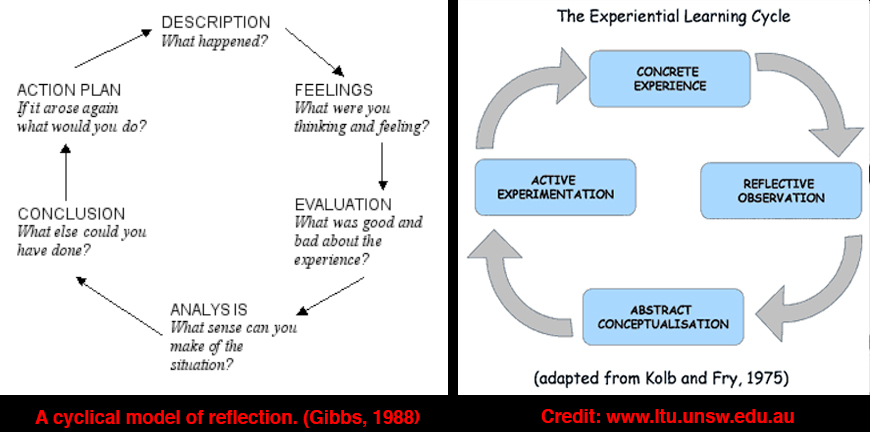

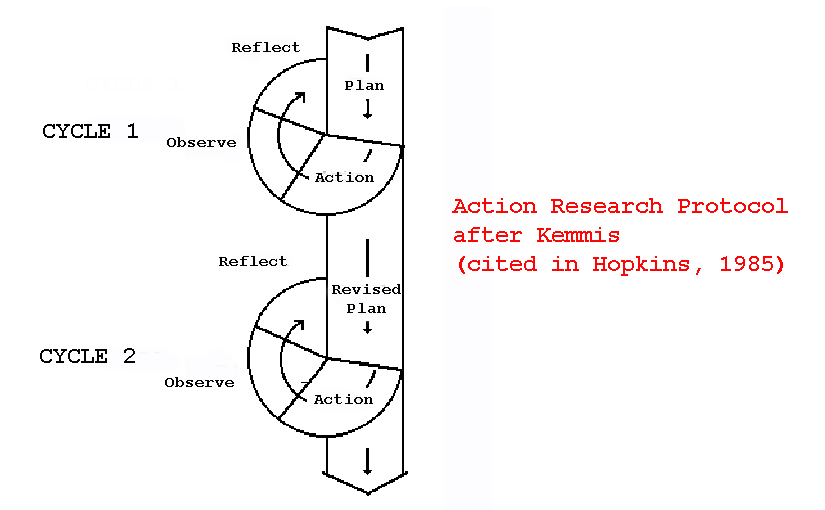

Developing Reflexivity in Research: The ‘reflexive turn’ is well documented in social science. Dr Christina Hughes provides an overview of the term reflexivity as it has been developed within various literatures (social science methodology, adult and organisational learning). An analysis of ‘four moments’ of reflexivity is given, together with practical discussion of developing reflexivity in relation to research.

Hughes discusses the relevance of:

Biographical aspects of researcher

values

motives

politics

employment

personal status’s

issues related to the key social divisions of age

gender

sexuality

ethnicity

ability as they specifically apply to the research

All knowledge produced through social research is imbued with these aspects of a researcher’s biography.

Class exercise: think about your biography. How might it impact and be part of your approach to your research. How does your biography affect how you see yourself and others, and how others wee you? Are you a black sheep? Does everyone see you that way or do they look at your haircut and see a poodle?